While researching

the Menu Decoder, we found ourselves looking into a lot of early cookbooks.

They’re good fun, and they can give insights into the past—the people’s past,

the story of everyday life—that no formal history can. Over the last few years

some good people have been putting many old texts online, in the original

languages and sometimes even in English translation.

Today

we offer a tribute to our forebear Maestro Martino da Como, the author of one

of the first printed cookbooks, the Libro de Arte Coquinaria. Martino was a boy from a small village in the Swiss-Italian Canton

Ticino who worked his way up cooking for princes and prelates, counts and condottieri, and eventually ran the kitchens of the Pope.

Martino lived in

interesting times. When he was busy at his cookbook, in the 1460’s, Cosimo de’

Medici and Francesco Sforza ruled in Florence and Milan, and Italy was getting

its first printing press. Pope Nicholas V statyed up nights planning the

rebuilding of Rome, and the terrible Turk was making himself at home in

newly-captured Constantinople.

They were good

times too, especially for anyone with a skill to offer Renaissance Italy’s sophisticated

elite. Consumption then could be very conspicuous indeed, and Martino had the

talent for coming up with unique culinary spectaculars. One recipe in the De

Arte informs us ‘How to Dress a Peacock With All

Its Feathers, So that When Cooked, It Appears To Be Alive and Spews Fire From

Its Beak’.

Italian cooking

has always had its divisions of class. One thing you won’t find in De Arte is

onions. Not much garlic either; as the Maestro frankly explains: ’Garlic and

onions are good for the peasants, who eat them willingly and depend on them

because of their poverty and because of the work they do’.

Surprisingly

though, many of the recipes he chose to include are simple, even humble: porchetta and sausages, cockscombs, peas and beans—even pastine in brodo. Not so long ago, every trattoria in Italy still had this modest dish on the

menu—plain broth with nothing but tiny noodles in it, mostly for people whose

digestion was telling them to leave the pasta alone that day. Five hundred years ago, Martino was

cooking it for the princes of the Church.

We like his idea of putting a pinch of saffron in the broth. We’re not

so sure about his recommendation to boil the noodles for a full hour—it seems

in Martino’s kitchen there was always a whole lot of boiling going on.

De Arte has its quirks; the casualness of his approach seems charming to a modern

cook: ‘To cook an egg, let it boil for the time it takes to say an Our Father’—per

spatio d’un paternostro. Precise quantities are

hardly if ever given. We cooks are invited to use secundo che pare a la tua

discrezione—‘as much as we think best’. He’ll tell

us to put in ‘the good spices’ but never says which ones they are.

Maestro Martino

certainly would have enjoyed a longer spice rack than most other cooks in his

day, but any upper-crust kitchen would have had saffron, ginger, mace, cumin,

nutmeg and the lemony peppery spice called ‘grains of paradise’ (or maniguette to the French, who once were very fond of it), as well as most of

the common garden herbs we know today.

Martino had an

interesting palette of flavours. The great chef is said to have spent some

early days in Naples, and there is definitely a sweet hint of the south in many

of his recipes: plenty of almonds and almond milk, as well as raisins and other

dried fruits. Another star ingredient is agresto

(verjuice), prominent in many soups and sauces. People in the Renaissance liked

a touch of tartness in their dinner more than in later ages. Verjuice is the

squeezings of unripe grapes, a kinder, gentler sort of vinegar. Maybe it’s time for this old favourite to

make a comeback; if you have a lot of grapes, there’s a recipe for making it

here.

Anyone with the

time to go through De Arte will find plenty of

fascinating sidelights and surprises. If you thought cheesecake was a modern

innovation you’ll see a perfectly serviceable recipe for it here: torta

bianca, made with lots of ricotta and flavoured

with ginger and rosewater. There are cheesecake variants too, including one

that calls for a pound of garlic (!)

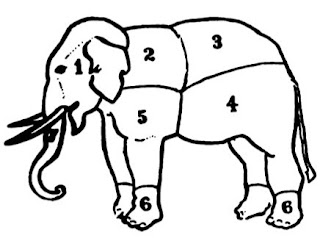

Maestro Martino’s

work lived on for centuries. Later editions, some good and some pennydreadfuls,

added whatever they pleased to the original recipes. One even included

(entirely fantastical) instructions on carving and cooking an elephant:

You can see the

whole text of De Arte Coquinaria here (in Italian) .

And a few of his recipes have been translated into English here.

There is also an English translation in print, though a flawed and

controversial one.

Online resources

are getting better all the time, and anyone with an interest in old recipes, or

anything else Italian, will be delighted to see John Florio’s 1611

English-Italian dictionary reproduced in a beautiful facsimile copy (thanks, Greg Lindahl!). Florio, a born

Londoner, was the son of an Italian refugee who became a great scholar and a

friend of Shakespeare; he spied on the French ambassador for Walsingham, and

did much to introduce the English to the arts and manners of Italy. For words

where Florio is no help, try the massive Tesoro della Lingua Italia delle Origini, a dictionary of Italian words going back

to the Middle Ages

No comments:

Post a Comment