Bonaparte has not got such a thing from all his thefts in Italy.

--Lord Elgin, writing in 1801 from Constantinople

It is Greece’s special sorrow that her War of Independence didn’t begin two decades earlier, before the fad for antiquities swept Western Europe – a fad that became an international art race when the triumphant Napoleon pillaged Italy and Egypt to fill his newly created Louvre museum.

But Thomas Bruce, the seventh Lord Elgin, ambassador to the Sublime Porte, trumped Boney to something even the Romans never thought of taking home: the sculptures of the world’s most famous building. Admittedly Morosini was the first to try, in 1687 – after he bombed the then-intact temple (even though he knew the Turks were using it as a powder store), he added insult to injury by removing the great pediment showing the contest between Athena and Poseidon as a prize to take home to Venice. The ropes broke as it was lowered, and the statues shattered into bits.

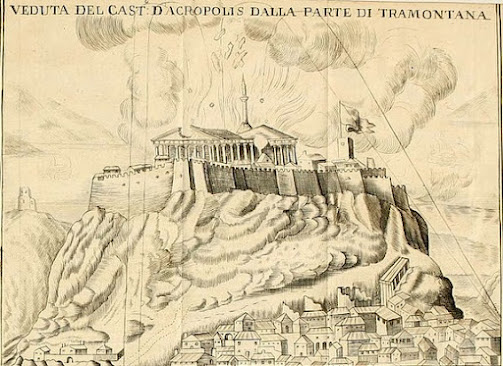

Elgin got his turn in 1801 when the Turkish military governor in Athens refused to let his artist, Lusieri, erect scaffolding to sketch the Parthenon frieze. Elgin went to the Sultan to get a firman, or authority, and the Sultan, pleased that the British had just rid Egypt of the French, readily provided one, not only allowing Elgin’s agents into the ‘temple of idols’ but to ‘take away any sculptures or inscriptions which do not interfere with the works or walls of the Citadel.’

Elgin interpreted this as a carte blanche, and sent Lusieri a long list of ‘samples’ to ship to London, all in the name of improving British arts by offering students back home a first-hand look at the greatest sculpture ever made. Besides, he wrote the Greeks ‘have looked upon the superb works of Pheidias with ingratitude and indifference. They do not deserve them!’

Considerable damage occurred to the marbles and to the temple’s structure during the removal; some panels were even sawn in two. In the meantime Naploeon’s agents were sniffing around Athens for any leftovers they could lay hands on.

Lord Byron was there when the last of the 120 crates were being loaded:

At this moment [3 Jan 1810], besides what has already been deposited in London, an Hydriot vessel is now in Piraeus to receive any portable relic. Thus as I heard a young Greek observe in common with many of his countrymen – for lost as they are, they yet feel on this occasion – thus may Lord Elgin boast of having ruined Athens.

An Italian painter of the first eminence, named Lusieri, is the agent of devastation. Between this artist and the French Consul Fauvel, who wishes to rescue the remains for his own government, there is now a violent dispute concerning a car employed in their conveyance, the wheel of which – I wish they were both broken upon it – has been locked up by the Consul, and Lusieri has laid his complaint before the Waywode.

Lord Elgin has been extremely happy in his choice of Lusieri. His works, as far as they go, are most beautiful. But when they carry away three or four shiploads of the most valuable and massy relics that time and barbarism have left to the most injured and most celebrated of cities; when they destroy, in vain attempt to tear down, those works which have been the admiration of ages, I know of no motive which can excuse, no name which can designate, the perpetrators of this dastardly devastation.

The most unblushing impudence could hardly go further than to affix the name of its plunderer to the walls of the Acropolis; while the wanton and useless defacement of the whole range of basso-rilievos, in one compartment of the temple, will never permit that name to be pronounced by an observer without execration.

Another eye-witness, Edward Clark, wrote in his Travel to European Countries (1811):

The lowering of the sculptures has frustrated Pheidias’ intentions. Also, the shape of the Temple suffered a damage greater than the one suffered by Morosini's artillery. How could such an iniquity be committed by a nation that wants to boast of its discretional skill in arts? And they dare tell us, in a serious mien, that the damage was done in order to rescue the sculptures from ruin...

Just as the Hydra sailed off to Britain with its cargo of marbles, another vessel arrived in Athens, carrying architect Charles Robert Cockerell, who, inspired by Elgin, was on his way to Aegina to strip the frieze off the Temple of Aphaia (which went to Munich instead).

Relief of Achilles and Pentheselia from Bassae, in the British Museum, CC by 2.0Even so, Cockerell managed to bag the marbles from the Temple of Apollo at Bassae; by then, Greek outrage at the plundering permitted by bribe-greedy Turkish officialdom had reached such a pitch that an armed band tried to hijack Cockerell’s caravan, only to be thwarted by a forewarned Turkish army.

Nemesis, however, is a Greek goddess, and she saw to it that Elgin got no joy from his deed. One of his ships sank near Kythera (although the marbles were expensively rescued by divers over the next two years). He faced constant ridicule from the British public, many of whom agreed with Byron on the issue; syphilis caused his nose to fall off, and he was divorced from his bubbly young countess.

The Elgin Marbles, by George Cruikshank, Wikipedia, CC0 license

On his way home to Britain he was taken prisoner in France for three years, on Napoleon’s orders. His marble-moving expenses totalled £63,000 (over £10 million today), a quarter of which was bribes to Turkish officials (this was at a time when the contents of the entire British Museum were valued at £3,000), but he managed to get only £35,000 from Parliament when it finally agreed to the purchase, in spite of members who condemned him as a dishonest looter, and he died in poverty.

The issue of returning the Parthenon frieze to Athens comes up periodically, for instance in 1941, when several MPs proposed it as a reward for Greece’s heroic resistance to the Nazis. Doubt, too, has been cast on old claims that Elgin ‘saved’ the fragile Pentelic marbles, by moving them into the London damp and smog (even Elgin noticed they were deteriorating, as he dickered with Parliament over the price). The current Greek campaign for the return of the marbles, begun by the late Melina Mercouri when she served as Minister of Culture, received a morale-boost in 1998, when William St Clair revealed in his Lord Elgin and the Marbles that the British Museum had ‘skinned’ away fine details and the patina of the marbles in 1937–8, when they used metal scrapers to whiten them.

Polls say that a majority of the British public want to return the marbles to Athens. The Greeks hope the beautiful viewing gallery on top of the Acropolis Museum with its windows overlooing the Parthenon itself will encourage the British Museum to send them back to where they belong.